Martha Graham

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

This article is about the choreographer. For the supercentenarian, see Martha Graham (supercentenarian).

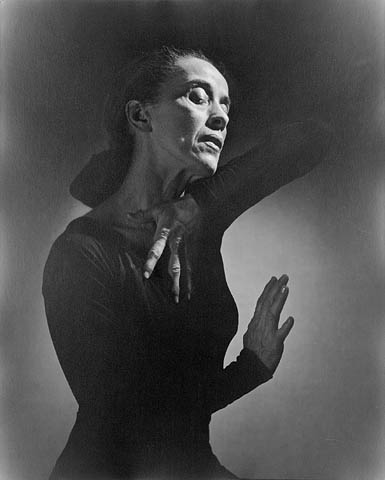

Martha Graham, shown here with Bertram Ross | |

| May 11, 1894(1894-05-11) Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, United States | |

| April 1, 1991(1991-04-01) (aged 96) | |

| American | |

| Dance and choreography | |

| Modern dance | |

| Kennedy Center Honors (1979) Presidential Medal of Freedom (1976) National Medal of Arts (1985) | |

Contents [hide] |

[edit] Early life

Martha Graham was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1894. Her father George Graham was what in the Victorian era was known as an "alienist," an early form of Psychiatry. The Grahams were strict Presbyterians. Dr. Graham was a third generation American of Irish descent and her mother Jane Beers was a tenth generation descendant of Puritan Miles Standish. With a physician's salary, the Grahams had a high standard of living. Dr. Graham often brought home to his wife strawberries in the dead of winter when they were very exotic and difficult to come by. Martha was strongly discouraged from considering any career in the performing arts.[citation needed]

[edit] A new era in dance

Photo by Yousuf Karsh, 1948

In 1925, Martha was employed at the George Eastman School of Design where Rouben Mamoulian was head of the School of Drama. Among other performances, together they produced a short two color film called The Flute of Krishna, featuring Eastman students. Mamoulian left Eastman shortly thereafter and Graham chose to leave also, even though she was asked to stay on.

In 1926, the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance was established. One of her students was heiress Bethsabée de Rothschild with whom she became close friends. When Rothschild moved to Israel and established the Batsheva Dance Company in 1965, Graham became the company's first director. In 1936, Graham made her defining work, "Chronicle", which signaled the beginning of a new era in contemporary dance. The dance brought serious issues to the stage for the general public in a dramatic manner. Influenced by the Wall Street Crash, the Great Depression and the Spanish Civil War, it focused on depression and isolation, reflected in the dark nature of both the set and costumes.

Her largest-scale work, the evening-length Clytemnestra, was created in 1958, and features a score by the Egyptian-born composer Halim El-Dabh. She also collaborated with composers including Aaron Copland, such as on Appalachian Spring, Louis Horst, Samuel Barber, William Schuman, Carlos Surinach, Norman Dello Joio, and Gian Carlo Menotti.[2] Graham's mother died in Santa Barbara in 1958. Her oldest friend and musical collaborator Louis Horst died in 1964. She said of Horst "His sympathy and understanding, but primarily his faith, gave me a landscape to move in. Without it, I should certainly have been lost." Graham's lighting designer Jean Rosenthal died of cancer in 1967.

Graham's dance style is based upon contraction and release of the body. She despised the term "modern dance" and preferred "contemporary dance." She thought the concept of what was "modern" was constantly changing and was thus inexact as a definition.

For a majority of her life Graham resisted the recording of her dances and would not allow them to be filmed or photographed. She believed the performances should exist only live on the stage and in no other form. At one point she even burned volumes of her diaries and notes to prevent them from being seen. There were a few notable exceptions. For example, she worked on a limited basis with still photographers, Imogen Cunningham in the 1930s, and Barbara Morgan in the 1940s. Graham considered Philippe Halsman's photographs of "Dark Meadows" the most complete photographic record of any of her dances. Halsman also photographed in the 1940s: "Letter to the World", "Cave of the Heart", "Night Journey" and "Every Soul is a Circus." In later years her thinking on the matter evolved and others convinced her to let them recreate some of what was lost.

Graham started her career at an age that was considered late for a dancer. She was still dancing by the late 1960s, and turned increasingly to alcohol to soothe her own despair at her declining body.[citation needed] Her works from this era included roles for herself which were more acted than danced and relied on the movement of the company dancing around her. Graham's love of dance was so profound that she refused to leave the stage despite critics who said she was past her prime. When the chorus of critics grew too loud, Graham finally left the stage.[citation needed]

In her biography Martha Agnes de Mille cites Graham's last performance as the evening of May 25, 1968 in a 'Time of Snow'. But in A Dancer's Life biographer Russell Freedman lists the year of Graham's final performance as 1969. In her 1991 autobiography Blood Memory Graham herself lists her final performance as her 1970 appearance in "Cortege of Eagles" when she was 76 years old.

Those who had the privilege of seeing her perform in her prime have attested to her precision, form and mesmerizing brilliance as a dancer on stage. Though she is arguably one of the most important choreographers in the history of dance (and perhaps one of the most important artists of the 20th century) she always said that she preferred to be known and remembered as a dancer. In the years that followed her departure from the stage Graham sank into a deep depression fueled by views from the wings of young dancers performing many of the dances she had choreographed for herself and her former husband Erick Hawkins. Graham's health declined precipitously as she abused alcohol to numb her pain. In Blood Memory she wrote:

It wasn't until years after I had relinquished a ballet that I could bear to watch someone else dance it. I believe in never looking back, never indulging in nostalgia, or reminiscing. Yet how can you avoid it when you look on stage and see a dancer made up to look as you did thirty years ago, dancing a ballet you created with someone you were then deeply in love with, your husband? I think that is a circle of hell Dante omitted.

Graham not only survived her hospital stay but she rallied. In 1972 she quit drinking, returned to her studio, reorganized her company and went on to choreograph ten new ballets and many revivals. Her last completed ballet was 1990's Maple Leaf Rag.

[When I stopped dancing] I had lost my will to live. I stayed home alone, ate very little, and drank too much and brooded. My face was ruined, and people say I looked odd, which I agreed with. Finally my system just gave in. I was in the hospital for a long time, much of it in a coma.

She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1976 by President Gerald Ford (the First Lady Betty Ford had danced with Graham in her youth).

Graham choreographed until her death in New York city from pneumonia in 1991 at the age of 96.[3] She was cremated, and her ashes were spread over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern New Mexico.

In 1998, Time listed her as the "Dancer of the Century" and as one of the most important people of the 20th century.

The most requested dance materials at the New York Public Library have to do with the work of Martha Graham.

Graham was inducted into the National Museum of Dance C.V. Whitney Hall of Fame in 1987.

[edit] Martha Graham Dance Company

See also: Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance

The Martha Graham Dance Company is the oldest dance company in America[4] and continues to perform, including at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center in June 2008, a program consisting of: Ruth St. Denis' The Incense; Graham's reconstruction of Ted Shawn's Serenata Morisca; Graham's Lamentation; Yuriko's reconstruction of Graham's Panorama, performed by dancers from Skidmore College; excerpts from Yuriko's and Graham's reconstruction of the latter's Chronicle from the Julien Bryan film; Graham's Errand into the Maze and Maple Leaf Rag.

[edit] Quotes

According to Agnes de Mille: text "I was bewildered and worried that my entire scale of values was untrustworthy. ... I confessed that I had a burning desire to be excellent, but no faith that I could be." Martha said to me, very quietly,

There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open. ... No artist is pleased. [There is] no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others."

from The Life and Work of Martha Graham[5]

"It was [Robert Edmond] Jones who used to say to his classes, Some of you are doomed to be artists. Martha picked up this phrase and used it many times thereafter. She also borrowed from him the phrase doom-eager, which he had borrowed from Ibsen."

from The Life and Work of Martha Graham[6]

[edit] Quotes from the public

- "Dancer of the Century"

1998, TIME Magazine

- Named as one of the Female "Icons of the Century"

1998, People Magazine

- "Brilliant, young dancer"

1998, New York Times

- "A National Treasure"

1976, President Gerald R. Ford